Nation and Sacrifice: The Akedah and Zionist Ideology

By Yael S. Feldman

Adapted from Glory and Agony: Isaac’s Sacrifice and National Narrative (Stanford University Press, 2010).

In his fascinating autobiography, A Life of Dissention, Max Brod (the famous best friend of Franz Kafka) tells a witty anecdote about his tenure as the dramaturge of Habima, then a relatively new Hebrew theater company in Palestine (later it would become the Israeli National Theater). Fleeing the Nazis, Brod left Prague and arrived in Palestine in 1939. His memoirs humorously evoke the overabundance of unsolicited biblical dramatic scripts he received at Habima (most of which never reached the stage):

After rejecting five plays named Moses, ten King Ahabs, and a dozen Ezras, I would have loved to hang on my door a sign that it is preferable to read the Bible in the original rather than getting excited over its staged versions.

Brod’s quip illustrates not only the popularity of the Bible in the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine, in the 1940s, but also the tension he perceived between the original and its rewritten versions, whether on stage or on the page.

But what this tension reflected was a more general unease — a palpable movement from adoration and fascination to altercation and subversion—in the relationship between Jewish nationalism of the past hundred years and the Hebrew Bible, particularly concerning the Bible’s role in molding modern, mostly secular, Jewish identity in the Land of Israel in the early 20th century.

It was the first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, who “elevated the Bible to the chief intellectual focus of the young state.”1 As a literary repository of ancient Israel, the biblical corpus functioned as a nation-building text, precisely like other ethnic myths that had been recovered and disseminated under the banner of European nationalism.

Despite the Bible’s historic religiosity, the attempt to co-opt it in the service of nascent Jewish nationalism is not entirely surprising. The pre-State pioneers’ secularization of an ancient body of mythical and historical tales that had ostensibly taken place in their new home established a line of continuity between their cultural past and their secular present. This search for connection affected all aspects of the Hebrew national secularist renaissance, impacting its language and letters, ideology and politics, aesthetics and ethics.

A case in point for the Bible’s persistence in the secular, nationalistic Israeli mind is the biblical narrative of the so-called sacrifice of Isaac. More than any other biblical narrative, the story of Isaac’s near-sacrifice, the Akedah, has become a focal trope of Zionist thought in Hebrew culture. Though in the early days of the Zionist revolution the Exodus from Egypt and the journey in the wilderness may have been serious contenders, they clearly lost the race in the wake of World War II and the struggle for independence. Since the 1940s, the Akedah has become a key figure in Zionist thought and Hebrew letters. Paradoxically, it gained its prominence because of its double semantic potential (like “korban,” it was understood to connote a state of “victimization” and/or “self/scarifice”), and came to represent both the slaughter of the Holocaust and the national warrior’s death in the old-new homeland. A case in point for the Bible’s persistence in the secular, nationalistic Israeli mind is the biblical narrative of the so-called sacrifice of Isaac. More than any other biblical narrative, the story of Isaac’s near-sacrifice, the Akedah, has become a focal trope of Zionist thought in Hebrew culture. Though in the early days of the Zionist revolution the Exodus from Egypt and the journey in the wilderness may have been serious contenders, they clearly lost the race in the wake of World War II and the struggle for independence. Since the 1940s, the Akedah has become a key figure in Zionist thought and Hebrew letters. Paradoxically, it gained its prominence because of its double semantic potential (like “korban,” it was understood to connote a state of “victimization” and/or “self/scarifice”), and came to represent both the slaughter of the Holocaust and the national warrior’s death in the old-new homeland.

The Akedah became part of Israel’s “civil religion,”2 articulating a modern ethos of national sacrifice. It was the heir of two ancient traditions of “noble” or “beautiful” death: on the one hand, the self-sacrifice of the armed modern Isaacs embodied the Greco-Roman model of warriors’ heroic death on the battlefield in defense of home; on the other, Isaac had long stood, at least since the Crusades, for the archetypal Jewish martyr figure, akin to martyrs in pagan and monotheistic religions, offered on the altar for the good of their people. Both of these traditions were folded into the ideology of Jewish nationalism. What began as early Yishuv pioneers’ generalized talk about heroic blood sacrifice gave way to a particular image—the Akedah—and to a very specific hero—Isaac.

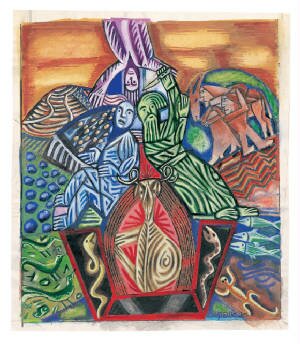

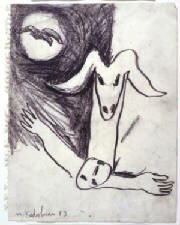

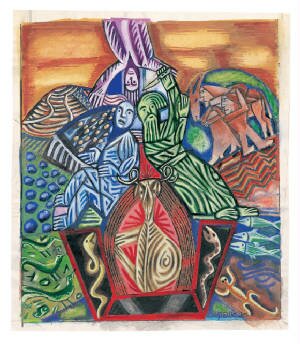

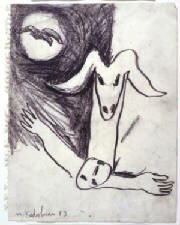

With Israel’s wars, the reliance on this image proliferated in Israeli art and letters. Take for example the paintings accompanying this article, as well as Shin Shifra’s succinct but poignant poem from 1962, “Isaac”:

No ram was caught in the thicket

For me.

I bound

And slaughtered.

God had no respect unto me –

He laughed.3

Here, the poet brazenly questions the necessity of national sacrifice. God’s laughter, which evokes Sarah’s famous laughter in Genesis upon learning she will have a son, becomes the malicious mockery of a god who accepts human sacrifice. In Shifra’s version, no angel will come to stay Abraham’s blade.

Even in the contemporary, post-Zionist context, this trope is alive and well in Israel. Its prolonged existence as a national theme to this very day throws a broad historical irony into relief: the fact that as a modern and secular national movement Zionism nonetheless appropriated this biblical narrative for their own purposes.

Though Israelis at large rarely stop to ponder this irony, its moral, psychological, and political significance has not escaped the attention of leading men and women of letters. Not unlike rabbis of old, contemporary Jewish authors are engaged in “making sense” of received scripture, practicing what has recently been termed “modern midrash”—“midrash” referring to rabbinic legends and homiletic interpretations of scriptures. Unlike the rabbis, however, they (or most of them) are doing this under the aegis of secularism.

Having never lost its weight in Hebrew culture, apparently the cultural and moral authority of the Hebrew Bible still counts—even for secular Israelis.

1Anita Shapira, "The Bible and Israeli Identity," in AJS Review: Recreating the Canon, 11-42.

2A term coined by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in The Social Contract.

3Translation by the author.

Yael S. Feldman holds the Abraham I. Katsh Chair of Hebrew Culture and Education and is a Professor of Comparative Literature and Gender Studies at New York University. Her research has been supported by international fellowships, and she had taught at Columbia, Yale, and Princeton Universities. Among her publications is No Room of Their Own: Gender and Nation in Israeli Women’s Fiction (Columbia UP), a pioneering study and a National Jewish Book Award Finalist; its Hebrew version, Lelo heder mishelahen, won the Friedman Memorial Prize. Her new study, Glory and Agony: Isaac’s Sacrifice and National Narrative (Stanford UP), from which this article is excerpted, is a National Jewish Book Awards Finalist in the category of Scholarship.

Adapted from Glory and Agony: Isaac's Sacrifice and the National Narrative by Yael S. Feldman. Copyright © 2010 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, www.sup.org. Find this book online.

Figure 1 (top): Avraham Ofek, The Sacrifice of Isaac, mid-1980s. Gouache on paper. Courtesy of the Ofek family.

Figure 2 (midway): Menashe Kadishman, The Sacrifice of Isaac, 1983. Drawings, pencil on paper. Florence, Gabinetto disegni e stampe degli Ufizzi. Courtesy of Menashe Kadishman.

|

|

|

Related articles...

Akedah Imagery and Hebrew Poetry in the Crusades

By Howard Tzvi Adelman

Jewtopias! The Jewish Romance with Communism, Zionism, and America

By Elliot Ratzman

Stalin's Forgotten Zion

By Zvi Gitelman

|

A case in point for the Bible’s persistence in the secular, nationalistic Israeli mind is the biblical narrative of the so-called sacrifice of Isaac. More than any other biblical narrative, the story of Isaac’s near-sacrifice, the Akedah, has become a focal trope of Zionist thought in Hebrew culture. Though in the early days of the Zionist revolution the Exodus from Egypt and the journey in the wilderness may have been serious contenders, they clearly lost the race in the wake of World War II and the struggle for independence. Since the 1940s, the Akedah has become a key figure in Zionist thought and Hebrew letters. Paradoxically, it gained its prominence because of its double semantic potential (like “korban,” it was understood to connote a state of “victimization” and/or “self/scarifice”), and came to represent both the slaughter of the Holocaust and the national warrior’s death in the old-new homeland.

A case in point for the Bible’s persistence in the secular, nationalistic Israeli mind is the biblical narrative of the so-called sacrifice of Isaac. More than any other biblical narrative, the story of Isaac’s near-sacrifice, the Akedah, has become a focal trope of Zionist thought in Hebrew culture. Though in the early days of the Zionist revolution the Exodus from Egypt and the journey in the wilderness may have been serious contenders, they clearly lost the race in the wake of World War II and the struggle for independence. Since the 1940s, the Akedah has become a key figure in Zionist thought and Hebrew letters. Paradoxically, it gained its prominence because of its double semantic potential (like “korban,” it was understood to connote a state of “victimization” and/or “self/scarifice”), and came to represent both the slaughter of the Holocaust and the national warrior’s death in the old-new homeland.